Why We Accept a Life We Constantly Need a Break From

When was the last time you returned from vacation and didn't immediately feel the creeping dread of the everyday grind? You unpack your bags, and before you even put the suitcase away, you're thinking about emails, deadlines, and routines. It's normal, we're told - everyone feels this way. But here's the question we seldom ask: Why is it normal? Why do we build lives we constantly feel the urge to escape from?

Our need for vacations reveals something deeper about the way we live. Consider the medieval peasant - often imagined as a poor soul laboring endlessly in the fields. Surprisingly, historians note that medieval peasants typically worked fewer hours annually than many of us do today. They enjoyed regular feast days and seasonal breaks. If even peasants from centuries ago had more leisure, why is it that today - with all our technology, machinery, and supposed advancements - we're expected to work more, not less?

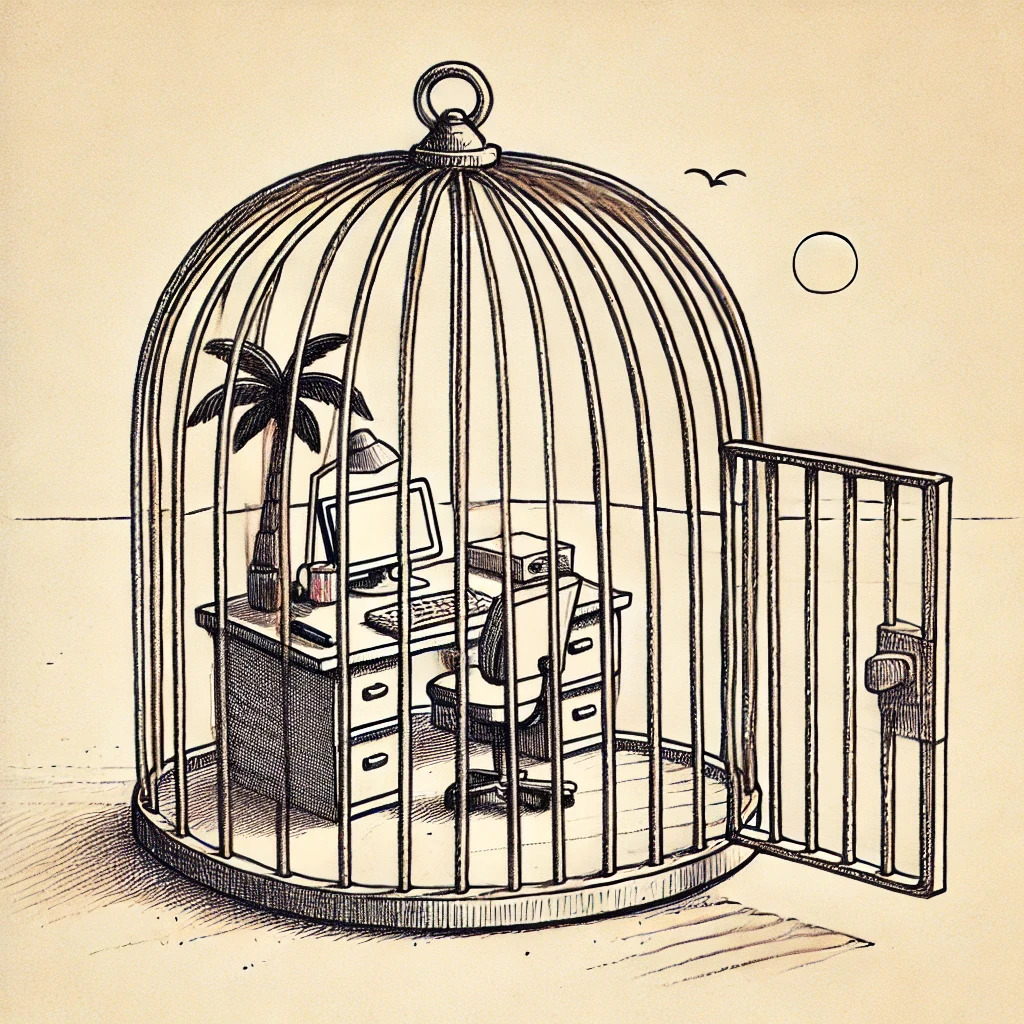

In his book "Ishmael", Daniel Quinn describes our modern lives using a powerful metaphor: the bars of our cage. But these bars aren't made of metal; they're composed of stories - narratives we repeat to ourselves so often they've become invisible yet powerful constraints on our imagination. We tell ourselves that life must involve constant labor and perpetual growth, that to slow down or reconsider how we spend our days is absurd or dangerous.

This narrative is precisely why the idea of doing less sounds radical or utopian. Immediately, people ask: "Do you want to live in poverty again? Do you want to give up your comforts, your smartphone, your healthcare?" But that's the story talking again. It assumes there's only one way forward - that more work always means more comfort, more convenience, more happiness.

Yet the data shows something entirely different. Economists like Jason Hickel highlight that after a certain point, the correlation between economic growth and societal well-being significantly weakens. Once a community reaches a reasonable standard of living, additional economic growth contributes less and less to overall happiness and health. At that point, why not channel our resources differently?

Imagine a scenario in which economic gains, instead of fueling endless consumption and production, are used to enhance public services and improve quality of life. Instead of working longer hours to afford the second or third car, we might prefer shorter workweeks and more time spent with family and friends. Rather than producing mountains of disposable goods, we could choose meaningful experiences, stronger communities, better education, and improved healthcare.

Sound idealistic? Consider Costa Rica, a country that deliberately prioritizes investments in public services over relentless economic expansion. Costa Ricans consistently report higher life satisfaction and happiness compared to countries with much larger economies but lower investment in social well-being. Their story proves a crucial point: another way is possible, and it's already happening elsewhere.

So why does the thought of slowing down feel so strange? Because the bars of our cage prevent us from imagining alternatives. We find ourselves trapped within narratives insisting that growth is linear, continuous, and essential. Our society's dominant story teaches that every gain in productivity must be immediately reinvested to produce even more. Economists call this the Jevons Paradox: efficiency gains intended to reduce resource use instead lead to increased consumption. When cars become more fuel-efficient, we buy more and drive further. When we streamline work processes, we use the freed-up time to add more tasks rather than reduce working hours.

But what if, instead, we consciously chose to break this pattern? What if the gains from increased efficiency were used not to produce more, but to work less, live better, and enjoy life more fully? Imagine if, instead of treating productivity like a treadmill that constantly speeds up, we treated it as an opportunity to slow down and enrich our lives.

Historically, our societies once recognized the value of rest and collective downtime. Public holidays weren't exceptions - they were the norm. Over time, however, these days of rest have quietly disappeared, replaced by the relentless logic that every free moment is an opportunity to produce and consume more. Today, proposing a new public holiday would be seen as absurd, an impossible luxury. Yet, we overlook that many of the advances that genuinely improved our lives - public health systems, universal education, infrastructure - were driven by deliberate public investments, not by endless cycles of production and consumption.

Moreover, consider that our current approach often rewards destructive outcomes more than beneficial ones. War and environmental disasters, for instance, generate enormous economic activity and GDP growth, yet clearly, these aren't desirable or beneficial states of affairs. On the other hand, caring for each other, community building, and ecological restoration offer profound benefits but are undervalued because they're difficult to quantify economically. Our measurements of success have become distorted, blind to what genuinely enriches human life.

Breaking free from the cage doesn't mean abandoning progress, comfort, or technological advancement. Rather, it means redefining what true progress entails. It means recognizing that beyond a certain point, more growth doesn't translate to more happiness or satisfaction. It involves shifting our collective imagination away from a single, unquestioned story toward a broader horizon, where multiple ways of living well are visible and attainable.

Admittedly, there's no single perfect solution - no neatly packaged utopia waiting just beyond our current worldview. But the very act of questioning and discussing these issues publicly and privately matters immensely. Opening up conversations about alternative visions of the good life, about what genuinely contributes to happiness, health, and community, is the essential first step. Without this discussion, we remain stuck, pacing back and forth inside our invisible cage, perpetually longing for escape but never daring to push open the unlocked door.

We don't have to choose between modern comforts and healthier, more balanced lives. With thoughtful planning and intentional change, we can have both. But first, we need to expand our imagination and dismantle the invisible barriers we've constructed. After all, why continue living in ways that constantly make us dream of being somewhere else, when we have the power to redefine what a good life truly looks like?